This article appeared as a Guest Editorial in the September 2016 issue of the European Journal of Person-Centred Healthcare

Most human beings, when ill, want to be treated in a way that is deeply respectful of their bodily needs and, more than that, all aspects of whom they are and where they come from. But in an era dominated by focus on the physical body, diagnosis, best practice algorithms, powerful technologies, time poverty, and cost escalation, ‘whole person’ approaches to patients are both hardly imaginable and a tall order for many clinicians.

But numerous clinical movements have grappled with providing treatments and care that address more than the physical body. These movements have different names, and examining these provides an understanding of the deep and complex issues that emerge when we try to treat people in a manner befitting whole persons.

First, it must be said that any process of naming is essentially reductive. We mean something (or many things) in the choice of name. If we name it this way, then it is not that way. And the people who do the naming bring to the process certain assumptions, which may or may not be declared or even obvious. I want to illustrate this by critiquing names that have been applied to types of clinical work that constitute attempts to address more than the body.

I will start with my own choices. In my first book, Somatic Illness and the Patient’s Other Story (1), I hinted strongly, by using that title, that if we look closely at people presenting with physical (i.e. somatic) illness we can frequently find vivid, personal, emotional, and relational stories that match the types of illness, as well as their times of development and perpetuation. In doing so I was declaring that it is not enough to consider just the bodily aspects of disease, and that my posture towards patients with illness and disease is primarily towards them as persons, rather than to a diagnostic task, though the latter should never be neglected.

But what do patients think about this? Human beings generally relate naturally and intuitively to stories. They have bodies, suffer diseases, and are storied beings. And the process of story-gathering has the potential to capture much of the non-physical aspect of disease. We find that attending to a patient’s unique individual story is a powerful approach to physical illness (1-7). Properly presented without stigmatisation it rings true with patients, but it is hard to sell to clinicians who are accustomed to mechanistic approaches and something less ‘warm and fuzzy’. But I am happy that the medicine I practice is full of story-gathering.

What makes up a story is itself a big story, but stories are certainly constituted by personal meanings. My second and more theoretical book was titled Meaning-Full Disease. How personal experience and meanings initiate and maintain physical illness (4). I see lots of meaning-full diseases in my clinic, and in practice routinely access peoples’ stories and the meanings and emotional nuances of these stories conveyed by language. Identifying meanings of illness is not a widespread practice but it does have a history, in both academic (7-14) and popular lay (15) writings.

In the practice of including a focus on story and meaning I repeatedly observe physical diseases that appear to be symbolic. In these instances both the disease and the patient’s story seem to say the same thing, express the same meaning. In such cases, the disease is both full of meaning and symbolic. A detailed theoretical approach that takes into account the phenomenology of symbolic disease has been presented elsewhere (7).

This is too restrictive. It suggests that all disease is symbolic. In the clinic I am unable to discern symbolic elements in all diseases, and if we were to accept that all diseases are both linked to our subjectivity and (more radically still) in some way symbolic then we have to grapple with the presence or absence of the symbolic in diseases in non-human species as well, which is a much greater challenge, though not insuperable (16).

It is much more important to recognise that the utility of these notions of story, meaning, and symbol, in patient care, emphasises the broader reality that when we treat patients with physical conditions we are treating persons whose realities comprise a fundamentally indivisible physicality (aka body) and subjectivity (aka mind). They are not separate and so we should not separate them in our practice of healthcare.

When we seek story or symbol in our desire to honour the subjectivity of our patients we soon learn that these newly revealed stories and symbols are doorways to the whole rather than magical reductive solutions in themselves, mainly because identifying the story is only the beginning of an engagement with the whole. I have had clinicians training with me who get very excited about the patient’s story and getting the meanings within, and constituting, the story, and then find themselves stymied because they do not know where to go from there (17) .

Narrative Medicine (see (18, 19)), a movement which has emerged in the last few decades, has much in common with our story-orientation. The narrative concept is very person-centred in that it honours how patients make meaning of their diseases, and how they respond to healthcare provision. But, ultimately, narrative medicine remains dualistic. The meanings it deals in are those that the patient brings to the illness, and which influence how he or she experiences both being unwell and the care that is given; that is, it deals in the meanings that arise for a patient in the context of having developed a biomedical illness. Such meanings are very important.

But I have not seen narrative medicine address meanings (or subjectivity elements) as being fundamentally crucial in the emergence of physical illness. That is, narrative medicine says quite accurately that an illness is very important for a patient, it is a socio-cultural and relational event and process, and it sits in a context of meaning. But the crucial point is that narrative medicine deals primarily with the patient’s and clinician’s response to an illness rather than in the meanings that actually predispose to and precipitate an illness.

Our story approach sees illness emerging in and out of and because of our stories, in conjunction with all the possible and various physical and environmental factors. While the terms story and narrative (in the context of illness and disease) both access elements that are quintessentially human, our story approach assumes that story is involved before the beginning of illness, is involved in the development of illness, and plays a role in triggering and perpetuating it. Narrative medicine will remain dualistic until it allows the story aspects to be present and influential at every stage, especially in the emergence and perpetuation of the illness itself.

Most stories are about what happens to us in our relationships, with our parents, primary carers, siblings, friends, authority figures, abusers, the wider community, culture, and the environment. Thus, our story approach opens up to be not just a focus on meaning but perhaps more fundamentally a focus on relationship. This includes, potentially, some kind of reiteration, in the relationship with the clinician, of the hurts and traumas the patient has experienced in their relationships through life, including those with previous clinicians. Herein, probably, lie the power of the despised placebo and the under-acknowledged nocebo elements of treatment.

Moreover, if healing is connected not only with stories and meanings but also with relational dynamics then a clinician must face his or her own relational capabilities. But I do not think that a title like Relationship Medicine would work when explaining what we do to a patient in a clinic, or when explaining our treatment modality to colleagues.

People commonly jump to conclusions. Our [1] work is sometimes misunderstood or too quickly identified with healthcare approaches that I either partially or fundamentally disagree with. Keeping it very simple, a principal feature of our work is about keeping the whole constantly in mind, whilst responding in a practical way to an aspect or part of the whole. Moreover, this work, of assuming and working with the whole, is done in ordinary healthcare settings (2), not in some elite bunker away from the mainstream. As can be seen immediately, this notion of whole does not and should not point to a reductive focus on story, meaning, and symbol, though it would be hard to deal with human wholes without these emerging.

If we start from this notion of wholes, an obvious naming contender is holistic (or wholistic) healthcare. What could be wrong with this? It seems made for the job. Ten years ago, when I was first establishing the AUT University post-graduate Masters programme in MindBody Healthcare, the term holistic was commonly identified (in the minds of university positivists and biomedical reductionists) with complementary and alternative healthcare methods, or ‘warm and fuzzy’ approaches with no solid evidence base. The local problem was that new university programs not only required approval from the AUT University committees, but also needed to be scrutinised by all New Zealand Universities and finally approved through a national Combined University Approval Process (the CUAP Committee). We decided it was prudent to choose a title for the course that did not constitute an undue risk of triggering academic prejudice and insurmountable opposition.

We felt significant constraints, but in the end chose MindBody Healthcare. We deliberately avoided the more usual configuration of Mind/Body because the ‘/’ between Mind and Body clearly signifies separation or compartmentalisation. Ironically, one of the external university reviewers for the programme protested that (s)he had ‘Googled’ the term MindBody, without the ‘/’, and found not one reference. In contrast (it was stated in that review), some 700+ references to Mind/Body appeared in his/her search. It was apparently highly suspicious that we were not following this ‘/’ convention, presumably because in an academic sense we were not ‘standing on the shoulders of giants’. And in a way the reviewer’s suspicions were justified. We were very deliberately erasing the ‘/’. We wanted to signify an absence of mind and body separation. The challenge was easily answered, and we received approval for our programme.

But the term MindBody is itself problematic in other ways. Whilst it intentionally conveys something of the non-split nature of the person, it also implies that the whole is entirely encompassed by notions of Mind and Body, thereby excluding soul, spirit, relationship, culture, environment, and anything else anyone cares to consider as a dimension of personhood. That was not our intention. MindBody is ‘code’ for the whole, at least for those of us who understand how it is being used. If one has to be an insider to know this then it does not really serve our call for holism in practice.

For these reasons, recently, I have drifted away from the use of MindBody, and describe what I do as a whole person approach. The re-direction of clinical gaze towards the person has been with us for decades. The development of the term person-centred is widely attributed to Carl Rogers and his client and person-centred counselling developed in the mid-twentieth century. It is now more widely applied in medicine and healthcare, for example in the activities of the Geneva Conference on Person-Centered Medicine. The difficulties that many of us have with naming are well illustrated in an excerpt from the report of the 2013 Conference[2]. The first thematic symposium of the conference focused on Innovative Person-Centered Concepts Research and concluded

‘with an analysis of the distinction between two frequently confused and conflated terms: personalized medicine (a reductionist biological approach) and person-centered medicine and care (a holistic scientific and humanistic perspective).’

The point to note is that the terms personalised (e.g. making sure each person gets the right dosage of a drug) and person-centred may sound similar but are based on very different assumptions.

The term person-centred care comes close in naming what we do. The problem is that a clinician can be person-centred and still dualistic in clinical practice. I know many clinicians like this. They are typically warm, concerned people with good relational skills and an aversion to the physico-materialistic reductionism of hard biomedicine. Yet, when it comes to allowing the patient’s story or symbolic elements to be important or even crucial factors in the development and adequate treatment of, for example, Crohn’s disease, psoriasis, crippling migraine, reflux oesophagitis, or cancer, they flinch, and avoid engaging with the whole.

For these otherwise often wonderful clinicians, accepting and responding to story, meaning, symbol or personal experience as actively participatory in triggering and perpetuating the disease is a non-dualistic step too far. Of course there are degrees of this. The point is that being person-centred does not necessarily mean being non-dualistic or committed to a strong concept of the person as non-dual or undivided. More importantly it does not guarantee the clinician will look at important story aspects.

Putting aside this problem of dualism for the moment, I favour the whole person approach or whole person-centred approach as a quick and understandable way of pointing to what we do. But, alas, the naming problems keep emerging.

This terminology does not adequately account for the kinds of larger wholes that embrace individuals, such as families, communities, and cultures. In a very real sense a person is not to be seen merely as individual. A person always exists in a larger whole. These larger wholes are inferred or actively engaged in the patient’s care, especially by clinicians who have a systems orientation, but less so by clinicians who have an orientation towards individuals, a dominant stance in Western health culture. In healthcare, we typically treat individual patients, not families or other larger systems.

But experience shows that illness and disease are not merely the outcomes of processes entirely within and concerning the individual. Although expressed in the individual who is diagnosed, disease emerges amongst many factors and elements including the wider story or collection of stories of the system(s) within which the individual survives, flourishes, or suffers. This is very hard for many clinicians. It is one thing to imagine that John’s ulcerative colitis is partly triggered by his personal stress problems, maybe even related to his break-up with his girl friend. It is quite another thing (unless one has a concept of the wider whole in all its intersecting elements) to imagine that John is actually ill because he carries, for example, generational and family trauma, on behalf of the system, and which needs attention, in some way, for him to get well. We may accept this in a condition like anorexia nervosa, but not for the wider spectrum of illnesses claimed by biomedicine, despite all the modern public health data relating health, illness, disease and longevity to factors like social support, economic status, occupational opportunity, stress, and altruism.

The term integrative, or integrative healthcare, can be quite compelling. I have resisted it, not wanting to be identified with those integrative approaches that are commonly a collection of disparate methodologies and skills thrown into a rather random mix, and then marketed as integrative. For example, there are groups all over the world that mix methodologies such as naturopathy, homeopathy, acupuncture, stress reduction, meditation and many other approaches. There are also health centres that have doctors, physiotherapists, counsellors, dieticians, pharmacists all working in the same location. These approaches are typically an integration of methods and clinicians’ roles, rather than a holding of the integration of the person. Many of them do not hold to a truly non-dualistic concept of personhood.

This is my concern about the common usage of integrative. Whole person approaches of the kind we advocate rely on a deep sense of the importance of holding an undivided concept of the person as we work with them. It does not mean we cannot diagnose or cannot focus on some aspect of the whole, but the notion of undivided-ness or non-dualism always remains present in our work. It is worth noting that a person is ‘always already’ integrated (perhaps in a dysfunctional way in illness), even if our healthcare concepts and provision are not.

Perhaps then we should call our approach non-dualistic healthcare. This would inevitably beg many questions, most of them philosophical, and probably bemuse many patients. Maybe its great virtue, apart from getting close to what we do, is that except for philosophers it would not trigger false assumptions or prejudices, at least to the same extent as the other terms so far surveyed.

It accurately represents the fact that while we must focus, in the clinic, upon this or that element of the whole, we are still claiming that physicality and subjectivity should be responded to as ‘one’, as co-emerging (7), as mutually co-constructing, as unable to be divided. And this does extend beyond the person into systems, because if we examine the issues closely it is impossible to say where communal and individual subjectivities start and finish.

This is the level of integration we are addressing. A flowing continuity between individuals and other individuals and groups of individuals and culture and the environment, in which mind, body, soul, spirit, relationship, family, personal and group histories, and belief systems all participate in that which is emerging as a health issue. It would surely require a multi-disciplinary team to address physical disease with all this in mind. Even if there were such a team, if it is fundamentally dualistic, and therefore does not allow story or subjectivity elements to be attended to in certain physical diseases, then it is not doing what we are doing.

In our approach we are not merely subscribing to the harmonious working together of various professionals or methods, however worthy that may be. We are not against multidisciplinary teams; it is just that these do not automatically reflect the level of integration we are addressing. Nor are they addressing the vital role subjectivity plays in the development of illness. Many multidisciplinary teams are highly dualistic in the sense of having little idea of the continuities between physicality and subjectivity.

The biopsychosocial approach of the psychiatrist George Engel (20) has been widely acknowledged. It is very clear that he envisaged biological, psychological, and socio-cultural factors as interacting in disease. This is very congruent with our work. Over the years I have done workshops with clinicians, and when they hear me talk they commonly say something like this: ‘ah yes, the biopsychosocial approach, I agree with that.’ But as I listen to them talk, and watch them in role plays, they clearly remain clinical dualists. They think body or mind. They certainly take time to be responsible in diagnosis, in thorough technological investigation, and in prescribing drugs. But generally they show little evidence of putting similar emphasis on the psychological and sociocultural factors, and if they do, it is often by referring the patients on to ‘mind’ clinicians who are equally dualistic. Clinicians often seem to pay lip-service to integration by using the term biopsychosocial as a kind of mantra, something they acknowledge but do not practice.

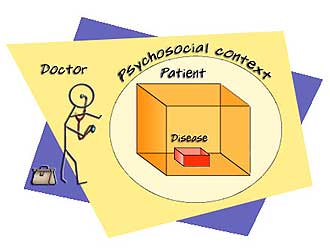

But the biopsychosocial perspective, whilst part of our approach, is also a little different. It focuses on biological, psychological, and social integration; again an integration of parts. I favour the opposite direction, a sitting with the whole and, from there, a focus on all the dimensions that are expressed by the whole, including bio, psycho, and social.

There is something quite different about an approach that combines separate territories to put the person together, from an approach that assumes we are ‘always already’ together. If the typical clinical usage of biopsychosocial had been more than a lip-service to the wholeness of patients by doggedly dualistic clinicians I could have adopted it. But, even so, we would still have to find room for other dimensions such as soul and spirit. In biopsychosocial these seem to be subsumed into psychosocial, as they are indeed in mindbody. Both terms have been configured by the secularity, physico-materialism, positivism, and scientism of our times.

We come now to the obvious territory and traditions of psychosomatic medicine. Addressing these at this point may offend some psychosomatic clinicians who may regard themselves as the natural ‘namers’ and proprietors of our territory. Surely this time-honoured specialty of psychosomatic medicine, largely dominated by the powerful disciplines of psychiatry and clinical psychology, deserves priority. But in my view the term psychosomatic is entirely inadequate, mainly because of what it has come to mean through the twentieth century.

The culture of psychosomatic medicine is solidly and systematically dualistic. Psychosomatic disorders are positioned as those illnesses that biomedical clinicians cannot explain. Hence we have had the term medically unexplained symptoms, until recently a major focus of conferences on psychosomatics. The dualistic foundations are clear to see just from this terminology. Our territory, so the psychosomatic narrative goes, is that which the body-only doctors, the physicians and surgeons, cannot manage or occupy with their biomedical explanations and measurements.

Thus we see the psychosomaticists treating mainly irritable bowel, fibromyalgia, chronic pain states, and chronic fatigue. It is rare to see an illness like rheumatoid arthritis or Crohn’s disease being discussed by psychosomaticists, at least in the way I would. I believe that these diseases require both the biomedical therapy options and an active addressing of the patient’s story. But this would not happen in most psychosomatic medicine clinics. This is because of the embedded dualism. Diseases such as Crohn’s or rheumatoid arthritis are considered to be fundamentally medical, and not psychosomatic. This idea that an illness is (can be) fundamentally physical rather than psychosomatic, fundamentally body rather than mind, is profoundly dualistic. Of course, there is acceptance in psychosomatic circles that stress (a physical concept originally) may make truly (sic) medical diseases worse, but often there is no real or deep sense that the physicality and the subjectivity of the person suffering from such a medical illness should be considered together, and from the beginning of treatment.

Sadly, psychiatry and psychosomatic medicine play active and powerful roles in maintaining lack of access by medical patients to a more whole person approach. Dualism, diagnostic reductionism, and traditional medical power structures substantially underpin these specialties and, as a hugely powerful combination, constrain whole person approaches to all diseases.

To the extent these clinicians claim to be not only the primary experts in the ‘mind’ side of illness, but also maintain a restricted focus on functional, medically-unexplained, psychosomatic and (more recently) somatic symptom disorders, they actively participate in maintaining the positioning of non-psychiatrist and non-psychosomatic clinicians, who can therefore justify simply treating diseases with drug and technological solutions without attending to the whole person. These latter clinicians are comforted, in the sense that if there is a whiff of mind-side difficulty they can call in these psychosomaticists, who will decide whether the patient John, with Crohn’s disease has a diagnosis of anxiety or depression, and perhaps help manage psychosocial difficulties. Both sides of this clinical role equation keep respectfully to their own side of the dualism. We end up with the bizarre, but completely understandable, situation in which a psychosomaticist will commonly not venture the idea that John’s Crohn’s disease might have something really important to do with the loss of his girlfriend.

More recently there has been a minor shift in psychosomatic terminology. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition (21), in its use of the term (Complex) Somatic Symptom Disorder, focuses on the co-existence of medically-explained and medically-unexplained symptoms in the same patient. This is not a very significant step. The underlying dualistic assumptions remain. And the clinician-centeredness of it is breath-taking.

My experience of working with clinicians attracted to this new DSM5 terminology suggests that it provides, firstly, an updated dualistic way of focusing on the many patients who defy easy diagnostic categorisation. Secondly, it represents a new energy and basis for addressing the ‘difficult,’ poly-symptomatic, difficult-to-categorize patients who bounce around the medical system consuming vast amounts of clinician energy and resources and generally get worse as they are repeatedly investigated from a purely biomedical perspective.

I do meet clinicians in the psychosomatic field with whom I can have fruitful whole person conversations, but there is little in these newer psychosomatic approaches to suggest that persons with medically explainable diseases are likely to get a whole person approach. The dualism in healthcare remains dominant. The focus on diagnosis and medical explanation remains. The reductionism to body-only for most physical diseases remains. The split between medically-explained and medically-unexplained disorders remains. And the vested interests whose training, careers and livelihoods rely on the dualism largely remain unchallenged.

I find it impossible to come up with a word or phrase that does the trick. We appear to need a super-word that combats clinical dualism and reductionism, is oriented towards wholes, and focuses on relations within and between wholes. It needs to accommodate physicality and subjectivity, bodies and minds and whatever else constitutes human reality. It will easily extend to stories, meanings and symbols. It will honour the role of diagnosis and biomedical treatments, and utilise these wisely. It should endorse a multidimensional approach to the whole person and his or her story and his or her relationships. This super-word or phrase does not exist. But whole person healthcare and story are definitely helpful.

Brian Broom MBChB, FRACP, MSc (Immunology), NZ Regd Psychotherapist

Consultant Physician (Clinical Immunology), Psychotherapist

Department of Immunology, Auckland City Hospital.

Adjunct Professor, Department of Psychotherapy, Auckland University of Technology

[1] I use ‘our’ to include myself and all the clinicians who have taught or trained in the MindBody Healthcare post-graduate programme at AUT University, Auckland

[2] http://www.personcenteredmedicine.org/docs/geneva06a.pdf